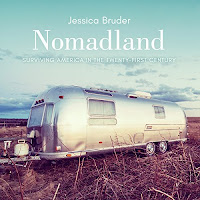

The Great Recession left many destitute, and some who had previously led middle-class lives found themselves homeless. Those who couldn’t find alternative shelter slept in their cars or RVs they bought in better times, or used what recourses they had left to buy used vans or small camp trailers. Most did this with the intension of resuming some semblance of their former lives as soon as they could. Some, however, embraced their new situation as an emerging lifestyle. They called themselves houseless rather than homeless, and they gladly left behind debt and mortgages, rent and jobs they hated for simplicity and the freedom of the road. Journalist Jessica Bruder spent several years interviewing hundreds of these people, followed the progress of a dozen or so closely, and even tried her hand at sleeping in her car for several months. Then she wrote a book called Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century.

Many of these new nomads are fifty or older. A lot of them are in their sixties and seventies. You might see them out on the road and think they’re retirees enjoying their golden years, but the truth is they have no conventional home to go to, and they often live hand to mouth. Because they’re older, there’s little chance of them finding high wage jobs. Some never had high paying jobs. Quite a few are loners.

The best places to camp without being disturbed or harassed by police is out in the country. That’s called boondocking. If you try to sleep while parked in a parking lot or on a suburban side street, that’s stealth camping, which is pretty risky. Some businesses, such as Wal-Mart, don’t mind if you stay in their parking lot for a night or two. And you can camp in state parks and national forests for free so long as you find a place where you can pull off the road. There’s another name for camping in a park outside of a designated campground: dispersed camping. You can usually stay in one spot for two weeks, and then you have to move, maybe at least 25 miles, depending on the area. Your car battery can be used to charge up your phone and tablet. You have to find a spigot to fill your water tank or water jugs. As for your bathroom needs, you have to bury your poop and use solar showers to keep clean. Backpackers will tell you that using baby wipes are better than toilet paper out in the wild, but you have to haul them out along with your other trash. Some use buckets lined with plastic bags. Truck stops and Laundromats sometimes have shower facilities you can use for a fee.

You need a fixed address to maintain a driver’s license, collect Social Security checks, and pay taxes and car insurance. You can do this by claiming to live with friends or relatives, along with a few other tricks.

In the warmer months, campgrounds hire camp hosts. You get a free campsite and maybe hookups for the season, and you get a small paycheck. In return, you have to pick up litter, clean bathrooms, answer questions, register campers and scold them when they make too much noise or break the rules. In November and December, you might find seasonal work such as selling Christmas trees or filling orders at an Amazon warehouse. Amazon calls their Christmas employees living in vans Camperforce, and they’ve even set up parking lots and facilities for them. So the next time you get a Christmas package from Amazon, think about the homeless grandmother who might have packed it.

One of the women Bruder stayed in contact with throughout her research period, a woman who was enthusiastic and optimistic about living on the road, finally bought five acres of desert land with money she earned at Amazon and was in the process of building herself an Earthship, which is a home made of dirt filled tires. She’ll use a cistern to collect rainwater, and she’ll use a compost toilet so she won’t need a septic tank. Her power comes from a generator and solar panels.

I find the whole thing both disturbing and somehow appealing. I’m a poor loner, and there’s little chance of me becoming independently wealthy. I live in fear of being evicted from my apartment. And I feel stuck in an arid town I don’t like. But what if moving was as simple as starting up my engine? And what if I could spend my summers in the woods?

I’ve even thought about buying a small piece of land out in the country and living in a used camper or an old school bus. I suggested I might do that after my father died, but everyone I talked to was horrified by the idea. “You can’t live in a camper!” they said. But they weren’t offering to give me a home.

No comments:

Post a Comment